This is part of an ongoing series from Ken Hensley. Read previous installments: Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Part VI

C.S. Lewis famously argued that our desire for things that cannot be satisfied by nature is evidence that we are more than merely the products of nature, that we are made for something beyond nature.

I think he was right. Even as it’s hard to imagine how or why a fish, born in water and living out its entire existence in water, would evolve the strong desire to fly in the air, or a bird to swim under the sea, it’s equally hard to imagine how or why a human being who, according to the atheist, is from top to bottom a product of nature, would evolve “naturally” strong desires that cannot be satisfied by nature. One of these is the desire for ultimate meaning and purpose; specifically, the desire that our lives have a meaning and purpose that transcends the few years we each are allotted on this earth.

This is something everyone wants.

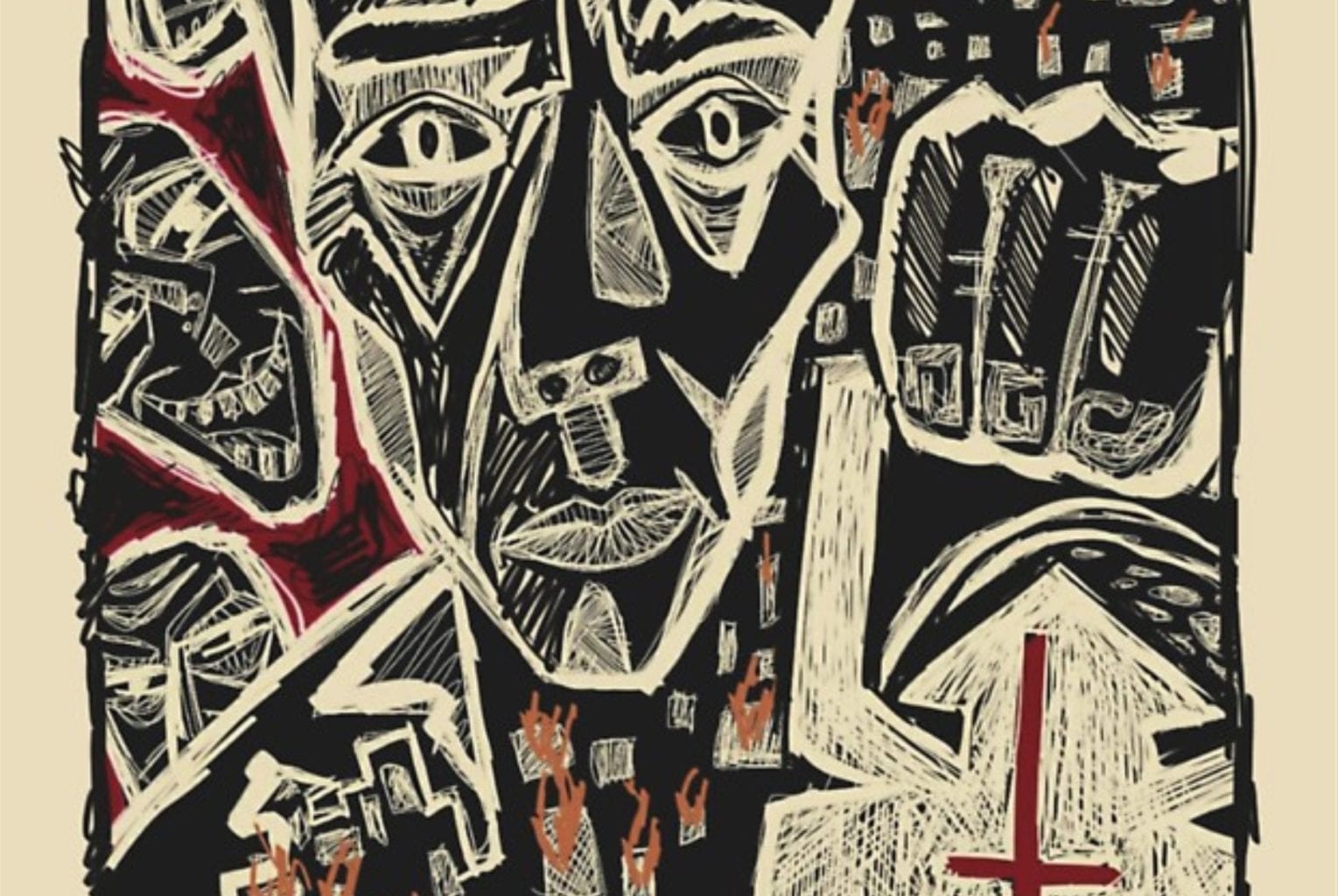

In his parable of The Madman, Friedrich Nietzsche, the father of modern atheism, faces squarely the implications of a world in which God has been eliminated, and he delivers the bad news. It isn’t pretty, but it’s honest and logically inescapable: a world without God is a world without objective meaning or purpose.

Have you not heard of the madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran to the marketplace and cried incessantly, “I’m looking for God, I’m looking for God!” As many of those who did not believe in God were standing together there, he excited considerable laughter. “Why, did he get lost?” said one. “Did he lose his way like a child?” said another. “Or is he hiding? Is he afraid of us? Has he gone on a voyage? Or emigrated?” Thus they yelled and laughed. The madman sprang into their midst and pierced them with his eyes. “Whither is God?” he cried. “I shall tell you. We have killed him — you and I. All of us are his murderers. But what did we do when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving now? Away from all sides? Are we not plunging continually backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there an up or down left? Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night and more night coming on all the time?”

Atheism and Meaning

The ultimate meaninglessness of a world without God is something, of course, that atheist philosophers readily admit.

For instance, Richard Dawkins, author of The God Delusion, agrees entirely with Nietzsche. Because God is a delusion and nothing exists but the material world, Dawkins draws out the logical implication: our universe is one with “no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference?”

It makes sense. If the entire material universe was not designed and has no purpose, then surely you and I, who, according to the atheist are nothing more than the accidental products of this material universe, were not designed and have no purpose.

Here’s how the late Harvard paleontologist Stephen J. Gould responded to the question, “Why Are We Here?”

We are here because one odd group of fishes had a particular fin anatomy that could transform into legs for terrestrial creatures; because the earth never froze entirely during the Ice Age; because a small and tenuous species, arising in Africa a quarter of a million years ago, has managed, so far, to survive by hook and by crook. We may yearn for a higher answer — but none exists.

I’m left wondering exactly how Dawkins’ expertise in biology, or Gould’s in paleontology, qualifies them to so confidently make such philosophical assertions — that there is no God and no higher answer to the question of human existence.

Who knows? Maybe one of the bones Gould was examining had imprinted on it: “This was not designed by God.”

When it comes to philosophers, probably the most important of the early twentieth century was the atheist Bertrand Russell. Here’s what he had to say about the meaning and purpose of life:

Man is the product of causes which had no provision for the end they were achieving; his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collisions of atoms; no fire, no intensity of thought and feeling can preserve the individual life beyond the grave; all the labor of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system.

Existentialist philosopher Jean Paul Sartre expressed the meaninglessness of human life when he said, “Death is the final absurdity which befittingly finishes off what the final absurdity of birth began.”

One of Sartre’s most famous books was appropriately entitled, “No Exit.”

Let’s be honest about this: If we are nothing but the accidental product of a universe that is itself nothing but chemistry and physics in motion, then Dawkins, Gould and Russell are entirely correct: there is no meaning or purpose to human existence.

The Optimistic Humanist Response

Some atheists appear to be bothered very little by this particular implication of their worldview. Then again, there are others who are driven to suicide when Nietzsche’s vision becomes clear to them.

Philosopher Albert Camus certainly didn’t believe the issue to be one of small importance. He thought the most important philosophical question of all to be the question of whether life has meaning.

In his book The Myth of Sisyphus, he wrote:

Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy .… I have never seen anyone die for the ontological argument .… Whether the earth or the sun revolve around the other is a matter of profound indifference .… On the other hand, I see many people die because they judge that life is not worth living .… I therefore conclude that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.

While some atheists avoid thinking about the ultimate meaninglessness their worldview implies, and some throw themselves off bridges, most attempt to resolve the internal tension by thinking along more optimistic lines:

So in the grand scheme of things, my life has no purpose. The kind of transcendent meaning offered by belief in God and our creation in the image and likeness of God does not exist. But surely this life includes some good things in which I can find meaning and satisfaction, even if only for a short time: in the goals I pursue, in the people I love, in the experiences I can enjoy. This is what I will focus on rather than the reality that ultimately I’ve come from nowhere and am headed nowhere.

This is what could be referred to as the optimistic humanist response. The more shallow and cynical version is contained in the blunt maxim: “Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die.” A more nuanced version goes more like this: “Live for today. Love the people around you. Find happiness where you can … and as for the ultimate meaninglessness of everything? Well, do your best to block that from your mind. It will only depress you.”

Camus wished with all his heart to avoid the total nihilism (“everything is meaningless”) of men like Nietzsche, and he fought against it all his life. But he could never entirely escape the nagging thought that the optimistic humanist position required a constant evasion of reality. He argued that by saying life is ultimately meaningless, but that we can create meaning for ourselves in the short time we have, we essentially commit philosophical suicide in order to provide psychological comfort in the present.

His conclusion was that life is simply absurd. If we kill ourselves to solve the problem, we get nowhere because death is as absurd as life. In the final analysis, all we can do is pursue the things that seem to make life meaningful, while knowing that, in the end, it all will be as though it never happened.

Meaning and Evangelism

Is it “natural” to believe that life has no ultimate meaning? Well, if there were no God, then yes, it would be entirely “natural” to believe that life has no ultimate meaning. Because it wouldn’t.

On the other hand, if God exists, if He created us in His own image and likeness to share forever the happiness of heaven, then life has ultimate meaning … and yes, it is perfectly “natural” for us to believe that life has meaning — and not merely a meaning we create for ourselves as we creep and crawl through an ultimately meaningless universe on our way to eternal nothingness, but a meaning that is real and true and something to treasure.

So how does this relate to evangelism?

The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches me that, whatever my atheist friend has come to believe about the non-existence of God, he is God’s creation. The nature and character of God has been etched into his being, he cannot really escape wanting a relationship with God and wanting there to be meaning and purpose in life.

The desire for God is written in the human heart, because man is created by God and for God; and God never ceases to draw man to himself. Only in God will he find the truth and happiness he never stops searching for (Catechism of the Catholic Church, para 27).

Because I believe this, when I talk to him about the problem atheism has in providing a foundation for belief that life has ultimate meaning and purpose, while I’m not presenting a “proof” for the existence of God or the truth of the Christian worldview, I am putting my finger on a point of tension that I believe exists within him.

If atheism is true, who can argue with Nietzsche’s madman as he challenges the townspeople to face the implications of having killed God? “Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night and more night coming on all the time?”

I’m banking on the belief that he will not wish to accept the implications of what he says he believes; that what is “natural” for him is to desire that life have ultimate meaning and purpose, to hope that it does, and maybe even to secretly believe that it does.

I’m banking on the belief that when he looks at those he loves — his wife, children, brothers and sisters, friends — he does not really believe that all their “hopes and fears … loves and beliefs” are, as Bertrand Russell put it, “but the outcome of accidental collisions of atoms.”

I’m praying that, faced with the brutal logical implications of the atheist worldview — that the universe and everything in it is ultimately meaningless — my friend may become more open to consider the rational arguments that do exist for the truth of a different worldview, one that makes sense of his natural desire that life have meaning, one that provides a basis for believing that life does in fact have meaning and purpose.

Up Next: How I Evangelize Those Who Doubt or Deny the Existence of God, Part VIII